Peace in the Middle East and Japan: On the Occasion of the 30th Anniversary of the Gulf War

Kunio Katakura, former Ambassador of Japan to Egypt, Iraq and UAE, Vice President of the Japan Arab Association

From the Autum Issue of the electronic “Salaam Quarterly Bulletin”, No.38, August 2021

We are now halfway through the year 2021. This year, for the first time in 124 years since 1897, February 2 was the last day of winter, and February 3 was the first day of spring both in the lunar calendar.

In terms of Japan’s relationship with the Middle East, this year marks 60 years since the start of independent oil development in 1960, and 30 years since the Gulf War. For me, it has been 60 years since I joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1960.

I have been able to overcome difficult times with a single-minded desire to be of service to Japan and the Middle East.

However, from the standpoint of Japan’s active involvement in the Middle East peace efforts, I strongly feel that we are now approaching a critical moment similar to going through the 8th station of Mt. Fuji, and I would like to share some of my thoughts here.

With the hot wind of the Look Middle East at my back

President Taro Yamashita receives King Saud on December 10, 1957. After several months of difficult negotiations, Nippon Export Oil Corporation and the government of Saudi Arabia signed a concession agreement for oil development in the concession area off the coast of the neutral zone between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

I joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1960. It was a time when the Look Middle East movement was gaining momentum around the world. After World War II, the world entered the Cold War era, and the world was being divided into two camps, the Western bloc led by the United States and the Eastern bloc led by the Soviet Union. Egypt was playing a leading role as the leader of the Third World. President Nasser succeeded in nationalizing the Suez Canal, which had been under the control of Britain and France, and emerged as a hero in the Arab world, greatly exalting Arab nationalism.

On the other hand, Taro Yamashita, president of the Arabian Oil Company (AOC) in Japan, backed by this Arab nationalism, acquired the mining concession of the offshore oil field in the neutral zone between Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in the Persian Gulf after repeated negotiations. I believe that this feat was a stroke of providence brought about by dissatisfaction with the British and American majors, the affinity of the Arabs with Japan, and the enthusiasm of Taro Yamashita. Moreover, Arabian Oil got off to a miraculous start in January 1960, when it struck an oil field in its first exploratory drilling. Taro Yamashita later

became known as “Arabia Taro”.

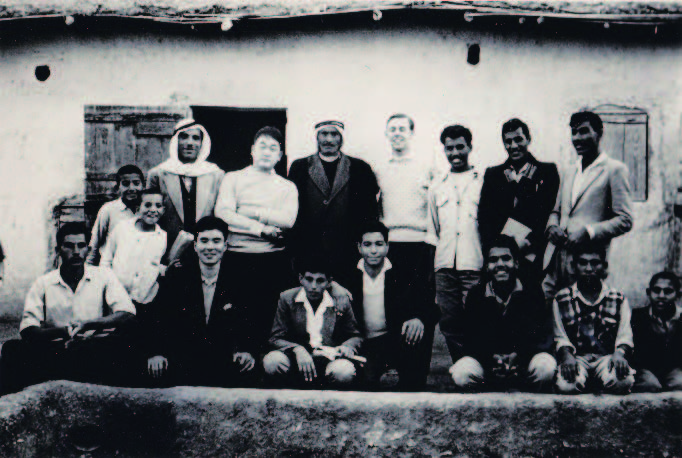

The photo above left shows a visit to a Palestinian refugee camp in Jericho during Arabic language training. In the back row, second from left is Mr. Kunio Katakura (1962).

The photo on the right is a poster for the movie “Lawrence of Arabia” starring Peter O’Toole.

I joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs immediately after the success of the independent development of the Hinomaru crude oil. Encouraged by the Arabian boom in the Japanese business world, I spent three years as an Arabic language trainee at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London, the Arabic Language Training Centre (MECAS) directly under the British Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) in Lebanon, and then at Cairo University. I was so impressed by the movie “Lawrence of Arabia” that I plunged into the scorching desert of the Islamic world in the Middle East without any calculation and studied Arabic and Farsi with all my mind.

At about the same time, Motoko (1937-2013), who would later become my wife, graduated from Tsuda University and began her studies at Cairo University as a Nasser scholarship student. After marrying me, she continued to research Arab societies as a cultural anthropologist while raising her children and living with semi-nomadic and semi-settled people, especially in Wardi Fathima, the hinterland of the Saudi holy city of Mecca, and focusing on the fieldwork she conducted during that time. For almost half a century, we have been working together with the people of the Middle East and the Islamic world. In traditional Arab societies such as Saudi Arabia, we men are not allowed to see or talk to women who wear a veil over their face and body. However, Motoko is invited to the women’s tent for weddings and other social occasions, and she is also free to enter and leave the men’s tent. Men have only one eye, but women have three eyes. Through Motoko, I was finally able to get a glimpse of Arab women’s society.

The First Oil Shock

Immediately after Israel’s independence, there were four wars in the Middle East between Israel and the Arab countries. The first oil shock is a phrase that signifies the global panic caused by the “Arab Oil Strategy”, a strategy set up by Egypt, a military power, and Saudi Arabia, an oil power, after the Fourth Middle East War, to force Israel to withdraw from the occupied territories by cutting supplies to oil consuming countries friendly or neutral to Israel. Some of you may remember that in Japan, there was an uproar over the buying of even toilet paper.

The Fourth Middle East War began on October 6, 1973, and no one could have predicted that the effects of the war would be felt in Japan like a tsunami. In addition, the Arab countries of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) unilaterally raised the posted price of crude oil by 70% in support of Egypt and Syria’s war against Israel. In addition, Saudi Arabia treated Japan as an “unfriendly country”, and the AOC was told that crude oil production would be cut by 10% from October 18 to the end of November, and that subsequent measures would be notified later.

The supermarket in the first oil shock in October 1973.

Asahi Shimbun, October 25, 1973

Market-Based Solutions

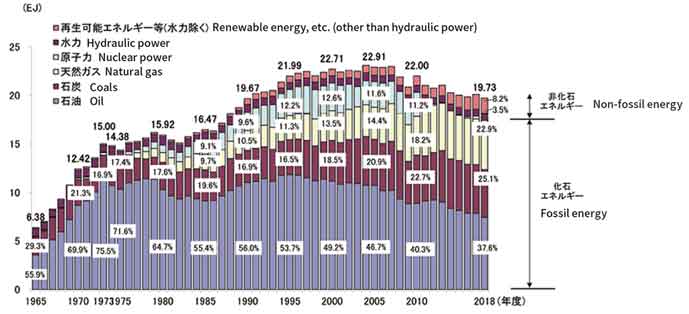

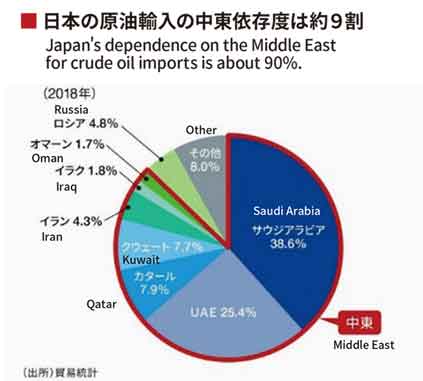

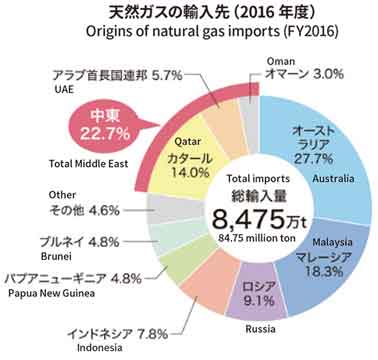

The two graphs below show the success of the “energy mix policy” proposed by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI, now METI) in overcoming the problem in crude oil imports and energy supply.

Crude Oil Imports by Country and Dependence on the Middle East

(Source: “Energy White Paper 2019”, Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry)

![Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iran, Other Middle East countries, China, Indonesia, Russia, Others,

Percentage of dependency on the Middle East (Right axis)]](https://g-salaam.com/images/2108_07.jpg)

Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iran, Other Middle East countries, China, Indonesia, Russia, Others, Percentage of dependency on the Middle East (Right axis)]

As shown in the graph, Japan has reduced its dependence on the Middle East for crude oil imports and has diversified its importing countries. Comparing 1973 and 1987, crude oil imports have decreased from 5 million barrels per day to 3.2 million barrels per day, and dependence on the Middle East has decreased from 77.5% to 67.9%. The graph below shows that in Fiscal Year 1973, 75.5% of the domestic supply of primary energy was dependent on oil, and that nuclear power, natural gas, and coal were promoted as alternatives to oil, and the development of new energy sources was accelerated. As a result, the share of oil in the domestic supply of primary energy has been significantly reduced to 40.3% in Fiscal Year 2010.

Trends in domestic supply of primary energy

(“Energy White Paper 2020”, Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry)

In this way, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) has paved the way to avoid the oil risk of the Basic Energy Plan, which is the foundation of the industrial economy, by adopting a mixed policy of reducing Japan’s dependence on oil as a primary energy source and reducing its dependence on Middle East crude oil imports.

Japan’s resource diplomacy under pressure

However, this energy mix policy alone will not help solve the serious problem that the oil-producing countries have forced on Japan, namely, that Japan is treated as an unfriendly country. The Arab side classified the crude oil importing countries into “hostile,” “neutral,” and “friendly” with regard to the Palestinian issue, and decided whether to impose a total export ban, a partial boycott, or the continuation of normal supply. Japan, at least, was treated as “not friendly” country. As a result, both Saudi Arabia and Kuwait notified the AOC that they would cut their supply by 5% per month, for a total cut of 10%.

The U.S., led by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, wanted to counter this with the concept of an “alliance of oil-consuming nations,” and Japan was asked to join the alliance. Japan has a background of focusing on economic development based on the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, and we cannot afford to undermine the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. On the other hand, unconditional entry into the U.S. scheme would be a betrayal of the friendship and trust that have been built between Japan and the oil-producing countries, and could cause a fatal rift in the relationship. Saudi Arabia’s notice to Japan that it would treat Japan as an unfriendly country was very serious.

In fact, the oil-producing country was pressing Japan on the principle of resource diplomacy. The principle was: (1) In order for Japan to secure direct trade in crude oil, it must cooperate in the industrialization and economic construction of oil-producing countries; (2) Establish a Middle East policy that includes the Palestinian issue. The oil-producing countries urged Japan that the principle of resource diplomacy was higher in priority than the market principle.

Miki Mission – Meeting with King Faisal of Saudi Arabia

In order to overcome this difficult issue, Prime Minister Tanaka decided to send a special envoy team headed by Deputy Prime Minister Takeo Miki. I accompanied him as an Arabic interpreter, and on December 10, we began our journey to eight countries in the Middle East. (For details, please refer to Kunio Katakura’s “Memoirs of an Arabist Diplomat in the Middle East,” Akashi Shoten, 2005, pp. 59-66).

Finally, our meeting with King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, one of the leading Arab oil-producing countries, was arranged and the king accepted our proposal for a knee-to-knee meeting (tete-a-tete) format with a small group of participants. The meeting was held in the Great Hall of the Royal Palace in Riyadh, with King Faisal, Abdul Wahab, the protocol director of the Royal Household, Mr. Takeo Miki, the special envoy, Mr. Kanji Takasugi, the Ambassador of Japan to Saudi Arabia, and myself and Mr. Hiroshi Shiojiri, an Arabic language specialist, acting as two-way interpreters.

Deputy Prime Minister Miki argued that the recent supply cut by the Arab oil-producing countries would not only be a great blow to Japan’s development as an advanced industrialized country, but would also have a negative impact on developing countries in Asia which receive economic assistance from Japan, and could eventually lead to the communist infiltration into them.

King Faisal listened with a nod of his head. The King condemned Israel’s occupation of Arab territories with the backing of the United States. In particular, he expressed his hope that the holy city of Jerusalem would be liberated and that he would be able to pray at the Aqsa Mosque, the third holiest mosque in Islam. Finally, he said, “Japan is a ‘friendly country’ for us.”

I think it was a good meeting where we realized that we Asians can understand each other if we talk to each other in a tete-a-tete setting. Nowadays, the “Arab boycott” is a thing of the past. There is a saying that “a drop of oil is a drop of blood”, and in the eyes of the Arab oil-producing countries, oil is literally their blood, not just a commodity. Oil is a vital resource that affects the very existence of a country, even if it is bought and sold depending on supply and demand on the basis of market principles. Even today, when it has become common knowledge that resource diplomacy means resource security, I believe that the lessons of that time should still be carefully passed on.

The Gulf Crisis

On August 2, 1990, Iraqi forces led by the Arab dictator Saddam Hussein suddenly invaded and annexed Kuwait, an Arab neighboring country. This was the Gulf Crisis. This August marks the 31st anniversary of the crisis.

It happened just as everyone around the world was beginning to hope that the Cold War would finally end with the fall of the Berlin Wall, and a new peaceful international order would emerge. The United Nations held an emergency Security Council meeting and adopted a resolution strongly condemning the invasion of Kuwait by Iraqi forces and demanding their immediate and unconditional withdrawal. (UN Resolution No. 660)

U.S. President Bush (then) met Prime Minister Thatcher of Britain which is Kuwait’s suzerain state, and on August 7, U.S. fighter jets and 4,000 paratroopers were dispatched to Kuwait. President Bush announced it to the nation via television.

In response, the Iraqi Revolutionary Council declared that Kuwait would be annexed and become the 19th province of Iraq. On the following day, August 9, the Iraqi Revolutionary Council announced that all foreigners staying in Iraq at that time would be banned from leaving the country and that all foreign embassies in Kuwait would be shut down by August 24. This was the start of the hostage operation.

246 Japanese in Kuwait

I arrived in Baghdad as ambassador on May 12, 1990, two years after the end of the Iran-Iraq War, which had begun in 1980 and continued for 8 years. Iraq was still in dispute with the Gulf States over the compensation it demanded to the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) for its losses. The situation was becoming increasingly tense and perilous. Then, on August 2, the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait in force.

The first thing we did was to evacuate the Japanese residents of Iraq, 71 of whom left the country on August 11 and 60 on August 13. On August 14, however, the Iraq announced that the Japanese, like the British and Americans, would not be allowed to leave the country.

A central task force on the situation in Iraq and Kuwait was established at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo. Remaining 246 Japanese nationals in Kuwait were reportedly evacuated to the embassy by 4:00 p.m. on August 7. However, on August 16, we were informed that the Iraqi occupation authorities in Kuwait have issued a notice that they will deprive all foreign embassies in Kuwait of their diplomatic privileges by August 24. The Japanese Embassy in Kuwait and the Japanese Embassy in Iraq were communicating back and forth via wireless telephones, so that we could get a rough idea of what was going on, and the instructions and orders of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs were transmitted to the Japanese Embassy in Kuwait via the Japanese Embassy in Iraq.

On August 17, the Speaker of the Iraqi Parliament, Ali Abdullah Saleh, announced that “the decision has been made to treat citizens of hostile countries as ‘guests’. Isn’t a “guest”, to put it bluntly, a hostage? But there was a feeling that the decision should be made carefully after seeing how it was actually applied. But if so, how should we deal with it?

On August 18, the Japanese Association Liaison Committee in Baghdad had a serious discussion. As a result, it was decided as the matter of policy that there was no realistic way to deal with the situation except to receive Japanese nationals residing in Kuwait by air in Baghdad, according to their respective company affiliation, and have them leave Kuwait via Baghdad.

Since the outbreak of the crisis, more than two hundred Japanese company employees, their families and travelers who had been sheltered in the Japanese Embassy in Kuwait and were operating a soup kitchen and living in groups, were transferred to Iraq under the direction of the Iraqi occupation forces, with the promise that they would be able to leave the country via Baghdad. However, this promise was broken, and by the end of August, they were dispersed and interned as “guests” at more than 30 strategic locations. I met with Nizar Hamdoon, the President’s aide and Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs (former Ambassador to the U.S.), to protest and criticize the hostage policy, and we had a heated discussion. (For details, see Katakura (2005), p. 151)

I cited the example of Saladin for his generous treatment of enemy prisoners of war, women and children when he fought the Crusaders, and criticized the Iraqi action, asking, “What happened to the pride of Saladin?” It is not sure whether this heated discussion had an effect, but Iraq announced release of women and children on August 26. On September 1, 70 Japanese women and children were able to leave Iraq safely by Iraqi Airways and fly to Amman, Jordan.

Last Minute Crisis Management and Measures for Hostage Release

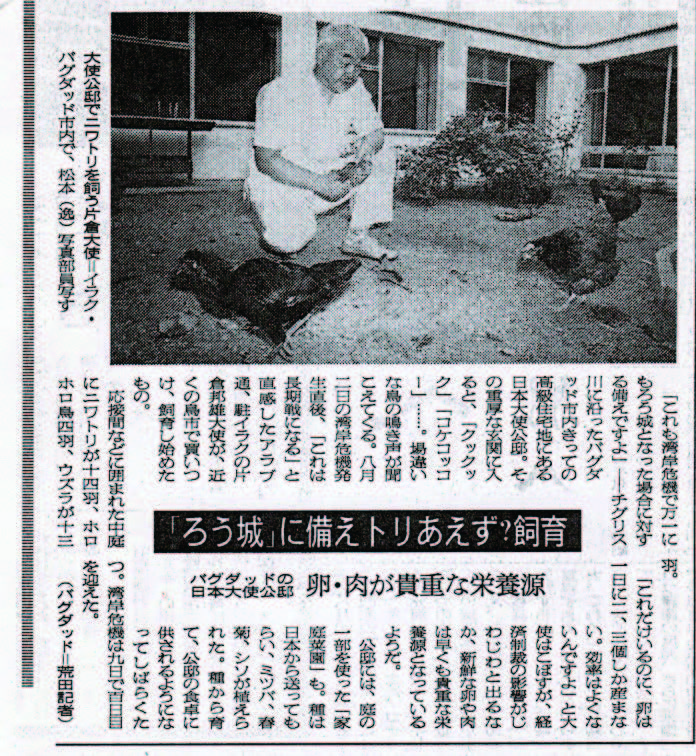

“Preparing for ‘Siege’ for the Time Being? Chicken Breeding”, Asahi Shimbun, November 10, 1990.

[Inside article:

We continued our struggle for the early release of the Japanese hostages. Those of us at the Japanese Embassy were confronted with the position of the Japanese government that Japan could not officially act individually to free the hostages because of Japan’s international solidarity with the United States and other countries. On the other hand, on the ground, we were struggling day and night to find a way to free as many hostages as possible by doing everything possible. We made up our mind, saying to ourselves, “There are risks involved in either way. There is no other way except choosing a lesser risk moment by moment.” It was around that time that we started keeping chickens, hollow birds and rabbits in the courtyard of the ambassador’s residence in preparation for a long siege. (Asahi Shimbun, November 10, 1990) Knowing our plight, then Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone and House of Councilors member Mohammad Antonio Inoki, among others, stepped up non-governmental efforts to secure the early release of the hostages.

Photo of my meeting with PLO Chairman Arafat when I was ambassador to the UAE. (In Abu Dhabi, UAE, 1987)

On November 3, a delegation of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), led by Prime Minister Nakasone and including Takayuki Sato, arrived in Baghdad. On November 4, they had a meeting with President Hussein. Mr. Arafat, chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), acted as an intermediary for the release of the hostages. Only Algeria and Palestine supported Iraq, which was isolated and branded as an aggressor by the United Nations. The Nakasone – Hussein meeting was set up with the backing of Arafat, who happened to be in Baghdad. The fact that I had a meeting with Chairman Arafat when I was the ambassador to the UAE may have been of some help.

Hussein had floated the idea of withdrawing Iraqi troops from Kuwait in exchange for Israel’s withdrawal from the occupied Palestinian territories, and perhaps Arafat had put the idea in Hussein’s ear during this visit.

Prime Minister Nakasone met with President Hussein three times for a total of four hours and forty minutes. During the “Tete-a-Tete” talks, they had a last minute delicate negotiation on how many hostages would be brought home. It is said that Hussein had his gun, which he always kept in his waistband, on the table beside him during the discussion. Prime Minister Nakasone later said that the atmosphere was similar to the Saigou-Katsu meeting at the surrender of Edo Castle. In the end, the mission succeeded in bringing back a total of 74 Japanese residents, mostly middle-aged and elderly hostages.

Subsequently, however, the movement to free the hostages came to a complete halt.

Hostage Release

Evening edition of Mainichi Shimbun, November 19, 1990, reporting the release of all hostages

Mr. Inoki was a man with unique ideas. He organized cultural and sporting events such as professional wrestling, basketball, and kite flying in Baghdad. He visited Baghdad many times because of his unique idea that “while these colorful events are going on, the fighting will not start and the hostages’ lives will be safe.”

By the time the countdown to the start of the use of force sanctions was underway, I could no longer sit still at the embassy. I had received information that Japanese hostages were being held in several oil-related facilities in the southern city of Basra, so I visited the oil-related facilities to ascertain their whereabouts and safety.

I was greeted by the plant manager who had stayed in Japan several years ago as an invited JICA expert. We were already on the war footing and on high alert, but the plant manager, after telling us about his pleasant experience in Japan, offered us a car to use freely for the tour of the plant. Thanks to this, we found some Japanese and Western hostages playing softball in a corner of the factory grounds and were able to talk to them through the barbed wire. We were able to get important information about the safety and treatment of some of them, and we were able to bring them some Japanese food and magazines. We named the plant manager “Togashi of Basra” (The checkpoint guard Togashi who detected a Buddhist worrier accompanying Yoshitsune as Benkei but let them go in the Kabuki play “Kanjincho”). In the midst of such a crisis in Iraq, I was reminded that the hearts of Arabs have something in common with the hearts of Japanese, and it has remained in my heart.

On November 18, the Iraqi Revolutionary Council announced the “release of all hostages,” stating that all hostages in Iraq and Kuwait would be released in stages within three months from Christmas. Nevertheless, a condition was attached to the announcement that there would be no incident to undermine peaceful atmosphere. It is assumed that the aim is to prevent the use of force in exchange for the release of the hostages, while keeping eyes on the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe meeting to be held in Paris from November 19. However, one of the reasons given for the release of the hostages was “requests from people of good will,” and the fact that the visits to Baghdad by former Prime Minister Nakasone, former West German Chancellor Brandt, and others were mentioned was certainly a ray of hope, even if the future of the hostage release remains unpredictable.

Resolution authorizing the use of force

On November 29, the United Nations Security Council adopted by a majority vote a resolution (Resolution 678) authorizing the de facto use of force against Iraq by January 15, 1991, as a last opportunity to urge Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait by any means necessary.

On the evening of November 29, just prior to the adoption of the UN resolution, President Hussein delivered a speech to the National Assembly in which he declared that he “condemned the Security Council’s move and that if the enemy launches a war, we will fight it resolutely.” On the other hand, at a press conference in Washington, D.C., on November 30, President Bush said that he would not engage in any discussions which would not achieve “the complete withdrawal of Iraq from Kuwait, the restoration of Kuwait’s legitimate government, and the release of all hostages in connection to his proposal for mutual visits by the U.S. and Iraqi foreign ministers after middle of December.

On December 4, Jordan’s King Hussein, Yemen’s Vice President, PLO Chairman Arafat and Iraqi President Saddam Hussein apparently met to discuss the Bush proposal.

On December 6, President Hussein issued a statement saying that he would propose to the Iraqi National Assembly that all foreigners detained and staying in Iraq and Kuwait be allowed to leave the country.

Gulf War – Operation Desert Storm

In response to Iraq’s announcement of the release of all hostages, U.S. President H.W. Bush said, “This does not change my view that Iraq needs to comply 100% unconditionally with UN resolutions,” and emphasized his commitment to the demand for Iraq’s immediate, unconditional and complete withdrawal.

On December 26, the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (GCC) held a summit meeting in Doha and adopted the “Doha Declaration” calling for Iraq’s unconditional withdrawal from Kuwait and the restoration of Kuwait’s legitimate government. On January 6, the three foreign ministers of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Syria issued a communique, saying, “Iraq’s efforts to justify the armed annexation of Kuwait by wielding the Palestinian cause are not acceptable. Iraq which continues adventurist policies does not qualify to discuss solution of the problems of the Middle East or security issues.” Although there were last-minute attempts to avoid war, the time period for the withdrawal from Iraq expired and UN mediation was terminated.

At 2:00 a.m. on January 17, 1991, under the command of U.S. General Schwarzkopf and Saudi Defense Minister Sultan Aziz, the Gulf War began, and the U.S. began bombing Iraq with Tomahawk missiles and F-15 aircraft (Operation Desert Storm).

At 4:00 a.m. on February 24, the multinational force made a full-scale invasion from the ground and sea, and the ground war began. The first multinational force to set foot in Kuwait included 4,000 Kuwaiti soldiers who had received military training in Saudi Arabia. Iraqi forces blew up and burned more than 700 oil wells and took Kuwaiti civilians as prisoners of war just before they escaped from Kuwait in defeat.

In the midst of the one-sided defeat, the state-run Iraqi Broadcasting Corporation carried a statement ordering the withdrawal of Iraqi forces.

On the same day, Kuwait was liberated and the Gulf War came to an end.

Upheaval in the Middle East repeated every ten years

After the Gulf Crisis and Gulf War, the turbulence in the Middle East continued. Terrorist attacks by Al Qaeda (bases) spread throughout the Middle East and Africa were carried out in many places, and the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States in 2001 shook the world. U.S. President George W. Bush declared a “war on terror,” which was followed by the Afghanistan War and the Iraq War. Aside from the Afghan war, the Iraq war was perceived by the proud Arabs as an imposition of American-style democracy. From this perspective, the Arab Spring was a movement for change that sought an Islamic-style democracy. However, the Islamic State (IS), which mistakenly practiced “jihad” (holy war) within the Islamic ideology, triggered civil wars in many Arab countries and gave the world the fear of indiscriminate terrorism.

At the behest of the new Iraqi government, the United States formed a coalition of the willing with the support of the United Nations, and in about three years, the Islamic State was effectively doomed to collapse. However, the spirit of peace and tolerance that had been built up as the essence and tradition of Islam, “Diwaniyah” (discussion in the wheelchair: Islamic-style democracy), was severely damaged.

On September 15, 2020, Israel, UAE, and Bahrain agreed to normalize diplomatic relations. At the White House (from YouTube by ITV News)

The normalization of diplomatic relations between Israel, the UAE and Bahrain was agreed upon in September 2020. In the long run, it can be said that peace in the Middle East has taken a step forward. However, we cannot rejoice in these agreements without reservation. How much will they lead to peace in the Middle East based on the premise of coexistence between Israel and Palestine? It is difficult to say. According to the joint statement, Israel said it would freeze its planned annexation of part of the occupied West Bank. I hope that a solution will be reached without leaving the Palestinians behind.

Japan’s Role in Middle East Peace and Reconciliation

For the UAE and Bahrain, it is an unavoidable diplomatic choice as they have to confront Iran, the center of the Shiite belt which spans from the Mesopotamian crescent, to Syria and ultimately to the Hizbollah forces in Lebanon, while having a large number of Shiites in their own country. In addition, they need the backing of the U.S. for the provision of new weapons, etc., and judging from the fact that it is essential to obtain the cooperation from Israel in advanced technology for economic and technological development in preparation for the post-oil era, it is presumed that they had no choice but to take this step even if they had to lower the flag of the “Arab cause”.

Japan has always believed that two-state coexistence of the Palestinian and Jewish peoples is the only way left. Based on this premise, Japan has always taken the lead in providing aid to Palestinian refugees and contributions to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Since around 2003, JICA in the area has been providing steady humanitarian cooperation in health fields, such as the issuance of maternal and child health handbooks, and environmental fields, such as the improvement of waste disposal.

Furthermore, Japan has expanded its perspective to the entire Middle East surrounding Palestine and Israel, and has planned and implemented its own broad-ranging projects with the ultimate goal of achieving peace in the Middle East. Let me give you two concrete examples.

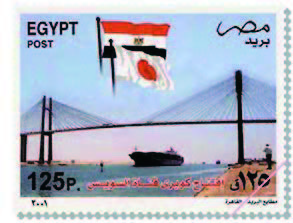

(1) Suez “Peace Bridge” (Photo: Former Japanese Ambassador to Egypt Kunio Katakura with the Suez Bridge, completed in 2002, in the background)

The ODA Japan-Egypt Friendship Bridge, featured in a foreign postage stamp: The Suez Canal, which is located at a strategic point connecting Asia and Africa, used to depend on ferry crossings. The construction of the Suez Canal Bridge with Japan’s grant aid has made it easier to travel between the two sides of the Suez Canal. A commemorative plaque depicting the flags of Japan and Egypt was placed in the center of the bridge. (From the ODA website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan)

The Suez Canal Bridge and former Japanese Ambassador to Egypt Kunio Katakura (2002)

A plan to build a 9 km long cable-stayed bridge over the Suez Canal was launched in Kantara, Ismailia Governorate, Egypt. The total cost of the project was about 11.7 billion yen, and it was agreed to be shared 60% by Japan and 40% by Egypt. The development survey was conducted in 1995-96, construction work started in 1997-98, and the bridge was opened in October, 2001. The bridge was named the “Peace Bridge” because it was expected to function as a major artery for the exchange of people, goods, and money from Cairo to Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Syria, and Turkey via the Gaza Strip in the northern Sinai Peninsula. I was stationed in Egypt at the time and worked hard for the agreement on this project to help bring peace to the Middle East.

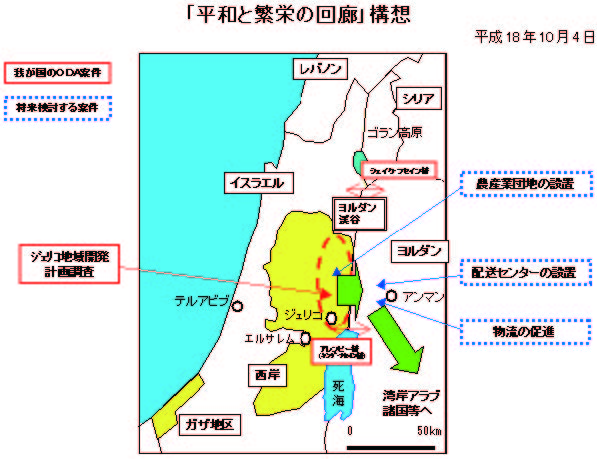

(2) “Corridor of Peace and Prosperity (Jordan Corridor)”

Press Release, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, October 4, 2006

This project is being carried out through the four-party talks among Palestine, Israel, Jordan, and Japan, and aims to develop the Palestinian private sector so that it can achieve economic and social independence. As its flag ship project, development of agricultural product processing facilities was planned and was scheduled to start operation in near future (as of October 2015). It was planned to export the products to Jordan and the Gulf countries, and it was expected to become a medium- to long-term initiative for coexistence and co-prosperity in the Middle East region. At present, however, there are still many obstacles, such as the promotion of occupancy by Palestinian companies and the development of logistics routes to overseas markets, which have held back the project. But with the recent normalization of diplomatic relations between Israel and the UAE/Bahrain, it is expected to progress smoothly. Such efforts by the Japanese government are expected to lead to a fundamental solution for the Israel-Palestine problem based on the premise of two-state coexistence in the long run (Takeshi Naruse, “Japan’s Middle East Policy and the Possibility of Japanese-style International Cooperation: Based on the Experience of Supporting Palestine,” World Peace Research Special Issue, “Peacebuilding and Japan’s Challenges” (Winter 2019), pp. 49-56).

Learning from History: Japan’s Proactive Role

The two cases mentioned above represent Japan’s unchanging proactive approach to the Middle East, which has accumulated historical achievements. Rather than simply relying on the military and diplomatic capabilities of the United States and Europe, Japan should contribute to the reconstruction of the Middle East in areas where it excels, as well as taking active responsibility for Japan’s defense capabilities.

Japan’s values of peace are not only highly regarded by the United States and Europe, but have also gained the trust of the Arab countries. Around the time of the first oil shock and the Gulf War, the negative image that Arab countries had of Japan (oil begging diplomacy, following the US) was almost completely wiped away.

Now is the time for Japan to make inroads into peacebuilding in the Middle East. Japan should make further efforts to build a “Middle East peace mechanism” from its own wide-angle perspective, mobilizing its soft power as Japan should. Middle Eastern countries, which are entering the post-oil era, will find it attractive to engage in multilayered exchanges with Japan, which has no political ambitions, not only in oil trade, but also in diplomacy, medicine, science and technology, and academic culture.

Japanese culture and Islamic culture happen to have developed in parallel in the same period of time, which means that they are connected by a mysterious bond. Prince Shotoku and the Prophet Muhammad were contemporaries in the early 7th century AD. At the time when the Islamic Ummah (nation-state) had established the concept of Salaam (peace) at the western end of the Eurasian continent, Prince Shotoku, at the eastern end of the continent, set forth the principle of “harmony is the key to nobility” in his 17-article Constitution. It can be said that both Islamic civilization and Japanese civilization have built-in opportunities for open dialogue of civilizations.

Expectations for Japan, like a hot wind from the Middle East, have returned after sixty years. The people of the Middle East have been welcomed into Japan. Mutual human exchange has increased greatly. I hope that the government will recognize this momentum correctly. And I hope that the younger generation will realize this.

(Based on Interview)

Middle East crude oil and natural gas still account for a large percentage of energy resources

Biography of Kunio Katakura

Born in Tokyo in 1933. From Miyagi Prefecture. Graduated from the University of Tokyo Faculty of Law in 1960 and joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He studied overseas at the University of London, MECAS (British Ministry of Foreign Affairs Arabic Language Training Center) and Cairo University as an Assistant Arabic Language Officer. He was Ambassador to the United Arab Emirates from 1986 to 1989, Ambassador to Iraq from 1990 to 1991, and Executive Director of the Japan Foundation from 1991 to 1994. He was Ambassador to Egypt for three years from August 1994. From 1998, he served as a government representative to the Second Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD2). He retired from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in January 1999 and was a professor of International Relations at Daito Bunka University from April 1999 to March 2004. He is currently Vice President of the Arab Association of Japan and Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Katakura Motoko Memorial Foundation for Desert Culture.